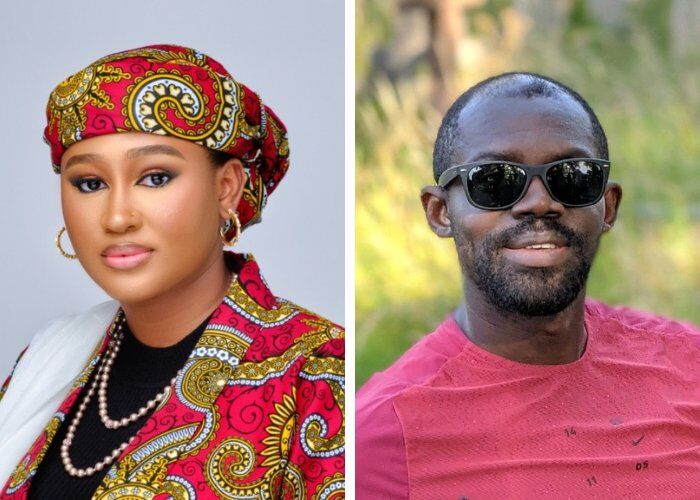

Surayyah Ahmad Sani (left) and Sanusi Ismaila

Interview with Sanusi Ismaila and Surayyah Ahmad Sani

CO-FOUNDERS, ADUNA CAPITAL

Northern Nigeria, a predominantly Muslim region, is home to about half of Nigeria’s total population. However, it garners just a fraction of the country’s startup funding. Estimates suggest 85% of venture capital funding is allocated to startups in Lagos, located in the southwest.

Sanusi Ismaila and Surayyah Ahmad Sani have co-founded Aduna Capital, which has recently announced the launch of its first fund. This $20 million fund aims to co-invest with other venture capital entities, primarily focusing on northern Nigeria.

Sanusi Ismaila is the founder of Colab, Kaduna’s first innovation hub and a significant source of technology talent in northern Nigeria. Surayyah Ahmad Sani is an entrepreneur, angel investor, and managing partner at UK-based TTLabs, a venture studio that also assists venture capital investors with on-the-ground due diligence on African companies.

The pair spoke to How we made it in Africa about investment opportunities in northern Nigeria and why they are bullish about backing entrepreneurs in the region. Below are slightly edited excerpts.

Tell us about how you founded Aduna Capital. Why the focus on northern Nigeria in particular?

Sanusi Ismaila (SI): We believed many of the stereotypes around northern Nigeria were wrong, and that there were bankable ideas and executors that weren’t getting funded.

Surayyah and I saw that most investors didn’t understand the culture and either wrote the region off or engaged with it wrongly. And we thought we could do better. We played around with some ideas, and eventually, it evolved into the fully-fledged fund that Aduna is today.

Could you explain the scale of opportunities in northern Nigeria?

Surayyah Ahmad Sani (SAS): Northern Nigeria is a massive market in itself. Over 60% of Nigeria’s current population is in the north, and 69% of Nigeria’s population growth is in the north.

So when you talk about the market in Nigeria that everybody puts in their pitch decks, you have to include northern Nigeria.

There are founders who are in a unique position to launch a product within northern Nigeria, and then expand to Africa and globally – those are the type of founders who we want to back.

You mentioned cultural differences. Can you elaborate on these and how they are relevant from an investment perspective?

SI: One of the overarching stereotypes about Nigeria is that it’s a low-trust society.

On the other hand, you walk into any public open market in northern Nigeria, and when it’s time to pray, the traders in any market would just walk out to the mosque and pray, leaving their stalls open with people inside.

There’s a whole system, particularly in open markets, where goods get supplied on credit. And this is happening informally. There’s no fancy accounting; in some cases, there are no sheets of paper, which I’ve always found fascinating. That doesn’t sound like a low-trust society.

Another thing about northern Nigerian culture is that there is a high social premium on humility and honour. There are some very successful software engineers or startup founders from northern Nigeria, but you wouldn’t hear about them a lot in the news.

On the other hand, in other parts of the country, as soon as someone has a pitch deck, they’re making as much noise as they can and trying to get into everybody’s faces.

In my experience investing in startups, I find those from northern Nigeria are much more efficient in using capital. And that comes in part, I think, from the cultural aspect.

There is this feeling of huge responsibility, that someone else has entrusted you with all this money and it is your fiduciary responsibility to deliver.

SAS: There is a trust factor that’s missing in the wider startup space right now.

It feels as if people have sort of cracked the system, right? They know what to tell you so they can get funded. And then when you fund them, investor money goes down the drain.

When you start to see the companies [Aduna Capital] is backing, you will wonder “Where have these companies been?” I always say, “They’ve been bootstrapping”, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. And now that they’re ready to scale, it is incredibly exciting to back them because they are very backable founders.

What kind of businesses are you looking to invest in?

SAS: We are in a funding winter right now and so there is a shift towards more sustainability, towards founders that can do more with less.

There is an agritech company we are looking to back – they’ve got over $4 million in GMV (the total value of goods sold on the platform) and are EBITDA positive, but they’ve never raised any external funding. That’s a massive opportunity.

There’s also an edtech company, with over 100 staff and more than $1.2 million in revenue, that’s looking to expand to other markets like Australia, the US, and the Middle East. But they’ve never raised.

So there are companies like this, incredibly sustainable companies, with really high-trust founders. They’re just not screaming out in public.

Which specific industries are most interesting to you when looking at northern Nigeria?

SAS: Lagos is more of a service-based economy, whereas the north is more manufacturing-based.

That said, fintech is one of the industries that is shining through.

For example, Sudo Africa [a card issuing and payments platform] is headquartered in Abuja, and has raised $3.4 million, and processed over $30 million in transactions. And they’re only just getting started.

Parts of northern Nigeria has significant agricultural potential. Can you talk about the opportunities in the agriculture sector?

SAS: I think agriculture is definitely a low-hanging fruit by virtue of the fact that most of the food in Nigeria, and much of the food in neighbouring countries, comes from northern Nigeria.

One area is agri-financing – giving access to finance to farmers and aggregators.

There are also a lot of untapped opportunities in transport and logistics around the agricultural value chain. We’re currently looking for companies in [B2B] fleet management that can go beyond northern Nigeria to neighbouring countries where these products are being delivered.

Northern Nigeria is strategically placed to serve francophone Africa, another region where many venture capitalists are not looking; it’s surrounded by Cameroon, Chad and Niger.

We are definitely looking to see which products you can export to these countries, and not just Ghana and Kenya, where everybody else is already looking.

SI: Manufacturing and food processing are also massive. Tomato Jos in Kaduna are processing tomatoes into tomato paste and have raised venture capital funding.

Part of what we’re looking at is the scalability because we want companies that can scale outside northern Nigeria to other parts of Africa and by extension, globally. But there are a lot of local opportunities in food processing.

Do you think there are still opportunities in primary agriculture?

SI: I think there’s a huge opportunity for producing food for export from Nigeria. There’s a company called Veggie Plus that ships across Nigeria and stocks most of the large supermarkets. They farm strawberries and other vegetables like bell peppers, in southern Kaduna and Jos. I don’t know whether they export now, I think most of their business is domestic. But if I were to get involved with that kind of business, I think I would focus all their efforts on exporting. It’s a tough problem to crack, but the upside is worth pursuing.

There was someone who used to export bell peppers from Jos to the UK, particularly for Tesco. When banditry became such a big problem, he had to fold up the business. But I think opportunities like that do still exist.

There are also opportunities in agricultural extension where IoT and AI is used to make agric smart and reduce food waste. We are watching a few companies in this area that have started to make some progress.

There is a large leather industry in northern Nigeria. Do you see potential in this sector?

SI: A lot of the leather in Nigeria, including the product that’s exported for Louis Vuitton, comes from Kano. There’s a whole industry there that has been built over generations. So I think there is a lot of value there already.

But I’m not sure if they are capturing as much as they can.

One of the things that would be interesting to me is to see some production, some value addition, happen in Kano that can be exported.

There’s some interesting stuff happening in other regions such as Jos, like the Naraguta leather factory, just beside the university. It’s a business that’s been built over two or three generations. There’s also a huge leather market in Sokoto, though a lot of it doesn’t go into stuff like shoes and bags, but into mats and poofs.

So I think there’s opportunity for people to go in there, organise it and see how much more value they can extract.

For instance, in the case of Sokoto, the poofs and mats that they make are artistic enough to sell abroad because they’re handmade and every set is different. You could build a narrative around those products.

I believe there’s a project that is planning to tell the story of leather in Kano. I think they are actually in Kano shooting right now.

Are there any other interesting areas that you are looking at?

SAS: There’s also a lot of opportunity in edtech, simply due to the massive population and the current educational system in Nigeria.

We could argue that edtech has got potential all over the country, but arguably more so in the north because of its population. Everybody is trying to gain additional digital skills on top of whatever they’re getting from their regular schooling.

SI: If you were to look at say, informal cross-border forex or, informal capital transfers across sub-Saharan Africa, they’re dominated by people from northern Nigeria. Or if you look at things like the second-hand automobile market, these are also dominated by people in northern Nigeria.

These are people who have built informal networks that work. They’ve figured out how to move money across these countries, they figured out how to move cars across those countries.

SAS: There’s a company called Moonah.app, that came out of Entrepreneur First in the UK. And that’s exactly what they are trying to do – to digitalise this cross-border payments, starting with Kano State. One of the co-founders, Abdulhakim Bashir is from northern Nigeria.

Is it a question of digitising and formalising existing models that are already in place?

SI: The thing that we’re looking for is not necessarily people who just go and digitise businesses, because I think we have abstracted that idea to the point where it’s not really useful. We are looking for people who can figure out how to link this economic activity that’s already happening under the radar to the formal economic or financial space.

Let me give you an example. As part of our work on financial inclusion, we came across this lady who lives in rural Kaduna. We were trying to understand how people save money, and she told us that she saved money by buying beans. It made no sense to me.

She wasn’t buying beans at a large scale, she was buying like cups at a time. So if she had, say, a spare 1,000 naira, she would go buy beans from the market and take them home. And if she wanted money, she would sell the beans.

I thought, you know, this has to be one of the stupidest things I’ve come across. A couple of days later, I checked what the inflation rate was. And that’s when it actually made sense to me that she was storing her value in beans.

She was keeping track of food inflation, which at that time was around 19% (it’s higher now). The interest rates at my bank at that time were somewhere around 4%.

So then how do I convince that person that my product is the better product when she’s losing so much value?

The point is, no one thinks about things like that from the perspective of that woman. We just say, “Oh, she’s financially excluded. We need to get her to open a wallet or bank account.” But fundamentally, the product might not suit her needs.

So, off of that experience, my new thinking is – is it possible to leave these informal systems as they are, or maybe make them a bit more efficient, but provide visibility to structured financial systems?

Aduna is a tech-focused fund. But would you consider investing in startups that are not ‘tech’ businesses?

SI: Personally I’d say yes, particularly if we see the possibility of making that business more efficient using technology.

There’s a company on our radar based in Zaria that is making animal feed from farm waste. The amount they’ve been able to grow in the space of one year has been incredible considering that they still do everything manually – I mean, they’re still grinding these things with mortars.

These are businesses that we would take a good look at. But we’re also careful that we’re not just backing these sorts of businesses with money, but we’re bringing something to the table. We sort of understand tech, so if it’s a tech business, it can be easier for us to add that value.

SAS: I think what is important is to acknowledge that a lot of companies use tech to help their processes, without necessarily having customer-facing tech.

And if we see a company that is doing incredibly well, and there’s a chance to, say, introduce them to a technical co-founder that can streamline their processes with tech, that’s something that we could do without necessarily changing its core business.

Aduna Capital co-founder Surayyah Ahmad Sani’s contact information

Contact details are only visible to our Monthly/Annual subscribers. Subscribe here.